Defaults: Tools of choice architecture

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

TYPES OF DEFAULTS AND HOW TO SET THEM

Defaults are settings or choices that apply to individuals who do not take active steps to change them (Brown & Krishna, 2004). Collections of default settings, or “default configurations” determine the way products, services, or policies are initially encountered by consumers, while “reuse defaults” come into play with subsequent uses of a product. At the finest level, a single question can have “choice option default”, which on electronic forms can take the shape of a pre-checked box (Johnson, Bellman, and Lohse, 2002).

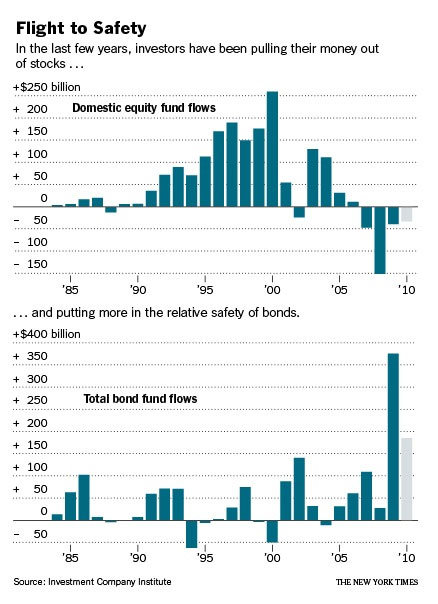

Defaults have been shown to have strong effects on real-world choices in domains including investment (Cronqvist & Thaler, 2004; Madrian & Shea, 2001), insurance (Johnson et al, 2003), organ donation (Johnson & Goldstein, 2004), marketing (Goldstein et al, 2008) and beyond.

They have a wide appeal among marketers and policy makers in that they guide choice while at the same time preserving freedom to choose. They are often regarded as the prototypical instruments of libertarian paternalism (Sunstein & Thaler, 2003).

Through default-setting policies, choice architects exhibit influence over resulting choices. The palette of policies includes simple defaults (choosing one default for all audiences), random defaults (assigning a configuration at random, for instance, as an experiment), forced choice (withholding the product or service by default, and releasing it only after an active choice is made), and sensory defaults (those that change according to what can be inferred about the user, for example, web sites that change language based on the visitor’s IP address).

Products and services that are re-used can also avail themselves of persistent or reverting defaults (which, respectively, remember or forget the last changes made to the default configuration) and predictive defaults (which intelligently alter reuse defaults based on observation of the user).

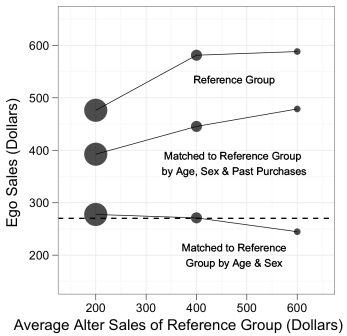

Those setting defaults should be aware of the ethical risks involved (Smith, Goldstein & Johnson, 2010). The ethical acceptability of using a default to guide choice has much to do with the reason why the default has an effect in the first place. When consumers are aware that defaults may be recommendations in some cases and manipulation attempts in other cases (Brown & Krishna), they exhibit a level of “marketplace metacognition” that suggests they retain autonomy and freedom of choice. However, if defaults are effective because consumers are not aware that they have choices, or because the transaction costs of changing from the default are too high, defaults impinge upon consumer autonomy. An often prudent policy, though not a cure-all, is to set the default to the alternative most people prefer when making an active choice, without time pressure, in the absence of any default. Running an experiment on a sample of the greater population can determine these preferences, and can be done in little time and at a low cost in the age of Internet experimentation (Gosling & Johnson, 2010).

REFERENCES

Brown, Christina L. and Aradhna Krishna (2004), “The Skeptical Shopper: A Metacognitive Account for the Effects of Default Options on Choice,” Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (3), 529-539.

Cronqvist, Henrik and Richard H. Thaler (2004), “Design Choices in Privatized Social Security Systems: Learning from the Swedish Experience,” American Economic Review, 94 (2), 424-428.

Goldstein, Daniel G., Eric J. Johnson, Andreas Herrman, and Mark Heitmann (2008), “Nudge Your Customers Toward Better Choices,” Harvard Business Review, December, 99-105.

Gosling, Samuel D. and John A. Johnson (2010), Advanced methods for conducting online behavioral research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Johnson, Eric J., Steven Bellman, and Gerald L. Lohse (2002), “Defaults, Framing, and Privacy: Why Opting In Is Not Equal To Opting Out,” Marketing Letters, 13 (1), 5–15.

Johnson, Eric J. and Daniel G. Goldstein (2003), “Do Defaults Save Lives?” Science, 302, 1338-1339.

Johnson, Eric J., John Hershey, Jacqueline Meszaros, and Howard Kunreuther (1993), “Framing, Probability Distortions, and Insurance Decisions,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 7, 35-53.

Madrian, Brigitte C. and Dennis F. Shea, D. F. (2001), “The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116 (4), 1149-1187.

Thaler, Richard, Daniel Kahneman and Jack L. Knetsch (1992), “The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion and Status Quo Bias,” in Richard Thaler, The Winner’s Curse, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 63-78.

Samuelson, William and Richard Zeckhauser (1988), “Status Quo Bias in Decision Making,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1 (1), 7-59.

Smith, N. Craig, Daniel G. Goldstein, and Eric J. Johnson (2010). Choice without Awareness: Ethical and Policy Implications of Defaults. Working paper.

Sunstein, Cass R. and Richard H. Thaler (2003), “Libertarian Paternalism Is Not an Oxymoron,” The University of Chicago Law Review, 70 (4), 1159-1202.