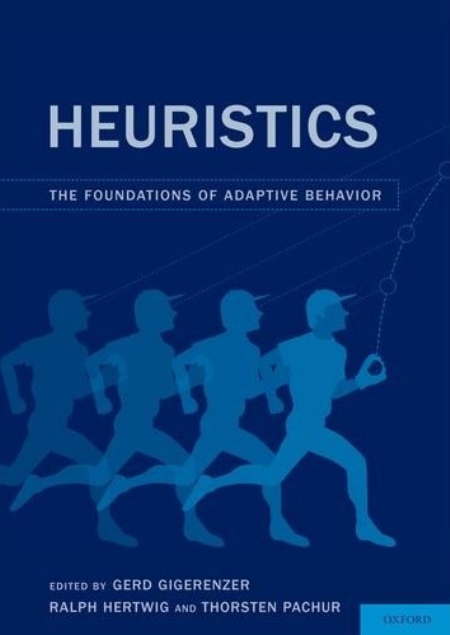

HOW DO PEOPLE MAKE DECISIONS WHEN TIME IS LIMITED, INFORMATION UNRELIABLE, AND THE FUTURE UNCERTAIN?

A new reader on heuristics, Heuristics: The Foundations of Adaptive Behavior , has just been released. Full disclosure, your Decision Science News editor is author on two of the book’s chapters:

, has just been released. Full disclosure, your Decision Science News editor is author on two of the book’s chapters:

CITATION:

Gigerenzer, G., Hertwig, R., & Pachur, T. (Eds.). (2011). Heuristics: The Foundations of Adaptive Behavior. New York: Oxford University Press.

PRECIS:

How do people make decisions when time is limited, information unreliable, and the future uncertain?

Based on the work of Nobel laureate Herbert Simon and with the help of colleagues around the world, the Adaptive Behavior and Cognition (ABC) Group at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin has developed a research program on simple heuristics, also known as fast and frugal heuristics. In the social sciences, heuristics have been believed to be generally inferior to complex methods for inference, or even irrational.

Although this may be true in “small worlds” where everything is known for certain, we show that in the actual world in which we live, full of uncertainties and surprises, heuristics are indispensable and often more accurate than complex methods. Contrary to a deeply entrenched belief, complex problems do not necessitate complex computations. Less can be more. Simple heuristics exploit the information structure of the environment, and thus embody ecological rather than logical rationality.

Simon (1999) applauded this new program as a “revolution in cognitive science, striking a great blow for sanity in the approach to human rationality.” By providing a fresh look at how the mind works as well as the nature of rationality, the simple heuristics program has stimulated a large body of research, led to fascinating applications in diverse fields from law to medicine to business to sports, and instigated controversial debates in psychology, philosophy, and economics.

In a single volume, the present reader compiles key articles that have been published in journals across many disciplines. These articles present theory, real-world applications, and a sample of the large number of existing experimental studies that provide evidence for people’s adaptive use of heuristics.

Review:

“This volume makes a powerful case for the importance of fast and frugal heuristics in explaining a wide range of aspects of cognition. It brings together the latest developments in one of the most influential research programs in the decision sciences, and will provide a valuable stimulus for, and a challenge to, research across the field.”

— Nick Chater, Professor of Cognitive and Decision Sciences, University College London

LINK

Amazon link to: Heuristics: The Foundations of Adaptive Behavior

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Appetizer

1. Homo heuristicus: Why Biased Minds Make Better Inferences.

Gerd Gigerenzer, and Henry Brighton

Part I: Theory

Opening the adaptive toolbox

2. Reasoning the Fast and Frugal Way: Models of Bounded Rationality.

Gerd Gigerenzer, and Daniel G. Goldstein

3. Models of Ecological Rationality: The Recognition Heuristic.

Daniel G. Goldstein and Gerd Gigerenzer

4. How Forgetting Aids Heuristic Inference.

Lael J. Schooler and R. Hertwig

5. Simple Heuristics and Rules of Thumb: Where Psychologists and Behavioral Biologists Might Meet.

John M.C. Hutchinson and Gerd Gigerenzer

6. Naive and Yet Enlightened: From Natural Frequencies to Fast and Frugal Decision Trees.

Laura Martignon, Oliver Vitouch, Masinori Takezawa, and Malcolm R. Forster

7. The Priority Heuristic: Making Choices without Trade-Offs.

Eduard Brandstätter, Gerd Gigerenzer, and Ralph Hertwig

8. One-Reason Decision making: Modeling Violations of Expected Utility Theory.

Konstantinos V. Katsikopoulos and Gerd Gigerenzer

9. The Similarity Heuristic.

Daniel Read and Yael Grushka-Cockayne

10. Hindsight Bias: A By-Product of Knowledge Updating?

Ulrich Hoffrage, Ralph Hertwig, and Gerd Gigerenzer

How are heuristics selected?

11. SSL: A Theory of How People Learn to Select Strategies.

Jörg Rieskamp and Philipp E. Otto

Part II: Tests

When do heuristics work?

12. Fast, Frugal, and Fit: Simple Heuristics for Paired Comparison.

Laura Martignon and Ulrich Hoffrage

13. Heuristic and Linear Models of Judgment: Matching Rules and Environments.

Robin M. Hogarth and Natalia Karelaia

14. Categorization with Limited Resources: A Family of Simple Heuristics.

Laura Martignon, Konstantinos V. Katsikopoulo, and Jan K. Woike

15. A Signal Detection Analysis of the Recognition Heuristic.

Timothy J. Pleskac

16. The Relative Success of Recognition-Based Iinference in Multichoice Decisions.

Rachel McCloy, C. Philip Beaman, and Philip T. Smith

When do people rely on one good reason?

17. The Quest for Take-the-Best.

Arndt Bröder

18. Empirical Tests of a Fast and Frugal Heuristic: Not Everyone “Takes-the-Best.”

Ben R. Newell, Nicola J. Weston, and David R. Shanks

19. A Response-Time Approach to Comparing Generalized Rational and Take-the-Best Models of Decision Making.

F. Bryan Bergert and Robert M. Nosofsky

20. Sequential Processing of Cues in Memory-Based Multi-Attribute Decisions.

Arndt Bröder and Wolfgang Gaissmaier

21. Does Imitation Benefit Cue-OrderLlearning?

Rocio Garcia-Retamero, Masanori Takezawa, and Gerd Gigerenzer

22. The Aging Decision Maker: Cognitive Aging and the Adaptive Selection of Decision Strategies.

Rui Mata, Lael J. Schooler, and Jörg Rieskamp

When do people rely on name recognition?

23. On the Psychology of the Recognition Heuristic: Retrieval Primacy as a Key Determinant of its Use.

Thorsten Pachur and Ralph Hertwig

24. The Recognition Heuristic in Memory-Based Inference: Is Recognition a Non-Compensatory Cue?

Thorsten Pachur, Arndt Bröder, and Julian N. Marewski

25. Why You Think Milan is Larger than Modena: Neural Correlates of the Recognition Heuristic.

Kirsten G. Volz, Lael J. Schooler, Ricarda I. Schubotz, Markus Raab, Gerd Gigerenzer, and D. Yves von Cramon

26. Fluency Heuristic: A Model of How the Mind Exploits a By-Product of Information Retrieval.

Ralph Hertwig, Stefan M. Herzog, Lael J. Schooler, and Torsten Reimer

27. The Use of Recognition in Group Decision Making.

Torsten Reimer and Konstantinos V. Katsikopoulos

Part III: Heuristics in the Wild

Crime

28. Psychological Models of Professional Decision Making.

Mandeep K. Dhami

29. Geographic Profiling: The Fast, Frugal, and Accurate Way.

Brent Snook, Paul J. Taylor, and Craig Bennel

30. Take-the-Best in Expert-Novice Decision Strategies for Residential Burglary.

Rocio Garcia-Retamero and Mandeep K. Dhami

Sports

31. Predicting Wimbledon Tennis Results 2005 by Mere Player Name Recognition.

Benjamin Scheibehenne and Arndt Bröder

32. Heuristics in Sports That Help Ws Win.

W.M. Bennis and Torsten Pachur

33. How Dogs Navigate to Catch Frisbees.

Dennis M. Shaffer, Scott M. Krauchunas, Marianna Eddy, and Michael K. McBeath

Investment

34. Optimal versus Naïve Diversification: How Inefficient is the 1/N Portfolio Strategy?

Victor DeMiguel, Lorenzo Garlappi, and Raman Uppal

35. Parental Investment: How an Equity Motive Can Produce Inequality.

Ralph Hertwig, Jennifer Nerissa Davis, and Frank J. Sulloway

36. Instant Customer Base analysis: Managerial Heuristics Often “Get It Right.”

Markus Wübben and Florian v. Wangenheim

Everyday things

37. Green Defaults: Information Presentation and Pro-Environmental Behavior.

Daniel Pichert and Konstantinois V. Katsikopoulos

38. “If …”: Satisficing Algorithms for Mapping Conditional Statements onto Social Domains.

Alejandro López-Rousseau and Timothy Ketelaar

39. Applying One-Reason Decision Making: The Prioritisation of Literature Searches

Michael D. Lee, Natasha Loughlin, and Ingrid B. Lundberg

40. Aggregate Age-at-Marriage Patterns from Individual Mate-Search Heuristics.

Peter M. Todd, Francesco C. Billari, and Jorge Simão

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)

Subscribe to Decision Science News by Email (one email per week, easy unsubscribe)