If you bet that you’ll lose weight, do you regain it when the bet is over?

A LONGER-TERM STUDY OF WHAT HAPPENS WHEN COMMITMENT CONTRACTS EXPIRE

A popular kind of commitment device is betting that you’ll lose weight.

At Decision Science News, we love the commitment devices. But, as we’ve have spoken about, we have mixed feelings about them, including the nagging concern that commitment devices may not lead to deep-seated changes or habit formation.

When the commitment device is gone, do the good habits remain?

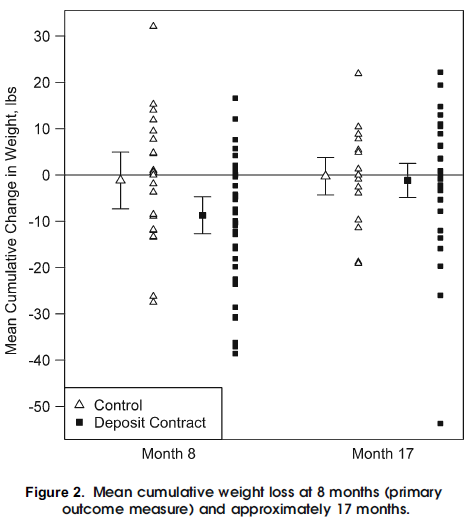

This week, we got some empirical evidence on that question. We were down at Penn, attending the Annual Symposium put on by the Penn CMU Roybal P30 Center in Behavioral Economics and Health, and Leslie John and colleagues presented a longer-run study spanning an eight month period during which a commitment contract was in place, and a follow-up period of 9 months. As the figure above shows, at Month 8 the devices worked: People lost about 10 pounds

But what happened when the commitment devices expired? When all bets were off, all the weight was regained (Month 17 in the figure above).

This is the first study we know of that looks at the longer-term consequences of commitment contracts. It’s hard to generalize from one study, but we think it shows that if you want a commitment device to work, you simply can’t let it drop. You have to keep renewing. So, if commitment devices are going to help folks, we need to find ways to get people to renew them. Or seek deep-seated changes so that people will do the right thing even when the device is absent.

REFERENCE

Leslie K. John, George Loewenstein, Andrea B. Troxel, Laurie Norton, Jennifer E. Fassbender, and Kevin G. Volpp. (2011). Financial Incentives for Extended Weight Loss: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-010-1628-y

ADDENDUM

Reader Alex V writes in with another experiment of this type, and one that does find longer run effects (at 12 months). We wonder if it is easier to stay off cigarettes than to stay off food. That is, quitting smoking is *very* hard, but once one has crossed over, perhaps it is easier not to relapse.

Put Your Money Where Your Butt Is: A Commitment Contract for Smoking Cessation

American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(4): 213-35, October 2010, with Xavier Gine and Dean Karlan.This paper tested a voluntary commitment product (CARES) for smoking cessation, where smokers were offered a savings account in which they deposit funds for 6 months, after which they take urine tests for nicotine and cotinine. If they pass, the money is returned; otherwise it is forfeited. 11% of smokers offered CARES take it up, and smokers randomly offered CARES were 3% more likely to pass a 6-month test than the control group.

The effect persists in surprise tests at 12-months. So this is just one more paper that looks at the longer-term effects of commitment contracts! (albeit not that far into the future).

Rumor had it that two of my former colleagues at McMaster (1970-74) signed a contract each Jan 1: If one of them caught the other one smoking before Dec 31, the smoker would pay $500. Every New Year’s Eve they got together, smoked (along with other indulgence I’m sure) until they were sick, and then renewed the contract for the next year. I think it worked, although possibly because of the effect of smoking itself when not addicted.

June 7, 2012 @ 10:13 am

[…] Yeah, usually. (Hat tip) […]

June 7, 2012 @ 10:50 am

We’ve been thinking the same thing! We’re about to introduce something on Beeminder called “pre-commit to re-commit”. Teaser post: http://blog.beeminder.com/weasels (which is also related to your conjecture that you don’t have to worry about much weaseling from the kind of people who like commitment devices).

And here’s my more snarky response to the objection that commitment devices don’t work long term, or are just a crutch:

I’ve been wearing glasses and contacts for *years* and it doesn’t help at all. As soon as I stop wearing them, I can’t see.

So, yes, commitment devices are a crutch and if you work out a way to not need them then that’s wonderful. But if they work they work. Beeminder (and StickK too, I think) tries to make it easy to have ongoing, open-ended commitment devices for incorrigible akratics like ourselves.

Commitment devices are also kind of the sledgehammer of behavior change. My view is that you should set up a commitment contract as an insurance policy. Then you should use other tools to try to make the commitment contract superfluous — create new habits, etc. It certainly sucks to need commitment contracts. But even worse than needing them is needing them *yet not using them*.

June 7, 2012 @ 3:29 pm

I remember reading a study (can’t find the reference though, so details might be off) which showed that any “short-term” weight loss mechanism was a failure in the long term: you ended up regaining weight.

This is very intuitive, but what was surprising was the definition of short-term: to prevent regaining weight, you need to stay at the new, lower weight for three years.

So maybe a 3-year commitment device would not need to be renewed?

June 8, 2012 @ 4:36 pm

I wonder whether these effects would be longer lasting if people found a way in which their self-improvements give them a new capacity. We know the endowment effect is strong, and robust to a variety of contexts.. perhaps individuals could become endowed with a new capacity.

I suppose the trick here is finding examples of things a person is currently unable to do, but CAN do with a bit of improvement along a focal variable.

In the domain of health (most comments have pointed toward weight loss or smoking cessation), the first thing I can think of is fitness performance.

The dream situation would be finding something that is mundane enough to be a part of our every-day experience. Maybe something like “the ability to climb two flights of stairs without becoming short of breath” might work–

If we explicitly test this (along with weight), individuals may be more inclined to make changes in their dietary habits when they notice changes along the capacity they’ve come to appreciate. Weight might matter a lot to most people, but my own sense is that this is because it’s a medium of measurement for other things we care about.

June 13, 2012 @ 12:14 pm