The difference between SPSP and SJDM

DECISION MAKING OR SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY?

There are those who consider the field of Judgment and Decision Making to be much like the field of Social Psychology, and others who find them as similar as vodka and water.

How can we, as the French say, préciser la différence?

Decision Science News has taken it upon itself to brew up a little textual analysis with the most recent conference programs of the Society for Judgment and Decision Making (SJDM) and the Society for Personality and Social Psychology (SPSP).

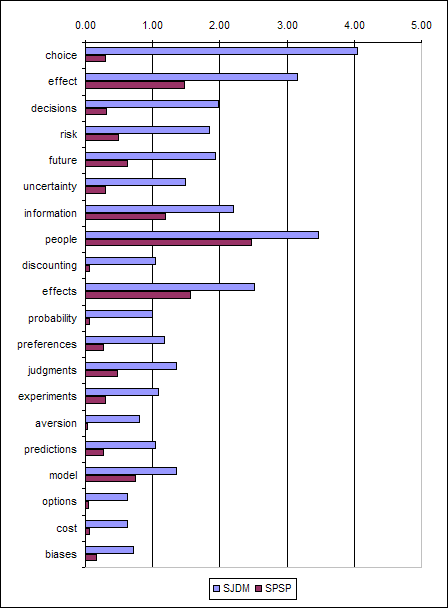

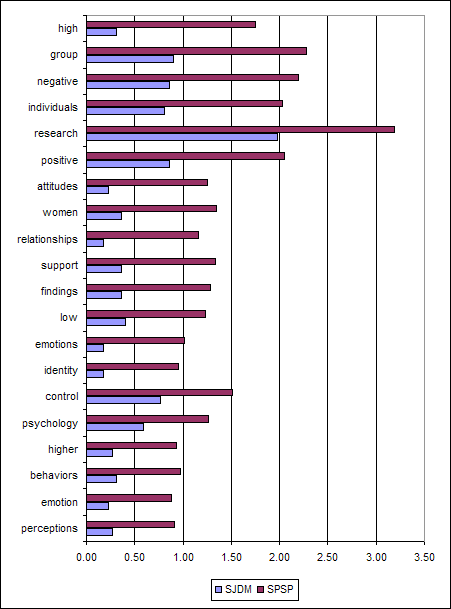

DSN counted how many times each word appeared in each program, then made a list of words that occurred in both programs, then deleted words that occurred three times or fewer in either program, then calculated for each word its rate per 10,000 words in each program, then looked at the words that had the greatest difference in the frequency of occurrence between programs, and then struck the uninteresting ones. Here are the results:

Words that are much more common in decision-making than in social psychology

(Rate per 10,000 words)

Words that are much more common in social psychology than in decision-making

(Rate per 10,000 words)

One can see not only differences in topic areas, but methodological differences as well (for example, social psych’s love of 2×2 ANOVA designs and median splits causes the words “high” and “low” to make it onto the list; perhaps this also explains why “positive” and “negative” appear).

Which field would you rather be in?

I would like to be in both. 😉 But I feel that I when I have to make a choice I would go with the less theorizing field of SJDM.

Thanks for clearing this up.

February 16, 2010 @ 6:35 am

Choose? I’m thinking integrate.

February 17, 2010 @ 1:10 am

They can’t be integrated as by default there can be one and only one priority in decision making & that is making the best decision.

Any constraints based on nebulous reasons about “people” or “attitudes” lessens your critical thinking ability just like any other self-imposed constraint.

It’s honestly odd… & maybe I’ll write about this later, but it’s odd people don’t understand that emotions are not helpful in making most decisions.

This doesn’t mean emotions are unimportant – they are for many reasons, like choosing a mate, buy the engagement ring, buying a house, buying a car… all these types of valuation decisions have emotional components.

If however I want to ask – what kind of health care reform would benefit the most people with the smallest amount of government interference?

Your emotions, my emotions, the President’s emotions are simply inconsequential.

February 20, 2010 @ 11:34 pm

Although you do want to take the emotion out of the equation in terms of your evaluation of the possible outcomes based on the assumptions you make, don’t you still need to make assumptions about how peoples emotional reactions to a decision could impact the possible outcomes, and if so wouldn’t that make emotions consequential.

February 22, 2010 @ 5:39 pm

Although the priority may be in making the best decision, you oversimplify the process by assuming that it is accomplished simply by identifying the best decision. An emotion-free analysis may help in identifying the best decision, but inclusion of emotions in studies may help to elucidate how people are currently making decisions and what may be required to implement the appropriate interventions.

This might be particularly germane if you are asking questions as to the President’s emotions — which can not be hand-waved away by the traditional rationalist approach of saying that people “on average” behave as according to rational models. If you are concerned with what the president is likely to do or in influencing the president’s opinion, you should be concerned about his emotions.

Consistent with your statement, emotions may be integral as part of individual utilities. A large though often under-stated rationale for health care reform is peace of mind. This is often why women have breast examinations earlier than is recommended by economic analysis.

Moreover, you eliminate a broad-class of decision-making realms by ignoring emotions, e.g., what decision-making processes lead to sexual aggression (and what are the appropriate interventions)? I’m sure a non-emotional analysis may lead us to answer what the best decision is, but it is unlikely to actually get us there.

Finally, if we accept bounds on human capabilities, then emotions have been cited as some to be (inconsistently) useful heuristics for decision-making. As such, emotions are helpful for decision-making if you take a more realistic viewpoint of the world.

This is not meant to deride “emotion-free” analysis and the wealth of information it can get at pointing us to what the best decision might be. However, it seems that by restricting ourselves only to these types of analyses, we would be imposing a “self-imposed constraint” that would — in a similar fashion — lessen our critical thinking ability. In fact, it is far easier to wish away emotions from our model then to actually address them.

April 26, 2010 @ 2:44 pm

As an interdisciplinary researcher (active in both social psych and cognitive psych/JDM), I find the reported “study” as missing the point. This data presented highlight differences in JARGON, not fundamental differences in the questions raised, nor NECESSARY differences in methodology used by these two fields of inquiry.

A healthy synthesis–one retaining the best of both fields and allowing for their independent contributions–would benefit all, not stifle either.

June 21, 2010 @ 11:28 pm

[…] http://www.decisionsciencenews.com/2010/02/15/the-difference-between-spsp-and-sjdm/ […]

October 11, 2010 @ 6:02 am

To me the use of normative models in JDM seems crucial. Social psychology is full of effects that are interesting because they seem to illustrate some sort of irrationality, just like all the effect studied in JDM. But many of the former, on close examination, turn out not to be irrational in any sense. They are fully consistent with some normative model. For example, some social psychology is concerned with “biases” for or against groups, but these biases turn out to be consistent with Bayesian probability theory. If we took social psychology as a guide for what needs to be fixed in our reasoning, we would end up fixing what “ain’t broke”. Of course, there is a lot of overlap between what gets published in JDM journals and what gets in social journals. And even much of what appears only in the latter does not suffer from the problem I raised here.

October 11, 2010 @ 12:54 pm