Judgment and Decision Making, Vol. 13, No. 1, January 2018, pp. 23-32

Thinking dynamics and individual differences: Mouse-tracking analysis of the denominator neglect task

Barnabas Szaszi*

Bence Palfi#

Aba Szollosi$

Pascal J. KieslichX

Balazs AczelY

|

Most decision-making models describing individual differences in

heuristics and biases tasks build on the assumption that reasoners

produce a first incorrect answer in a quick, automatic way which they

may or may not override later and that the advantage of high capacity

reasoners arises from this late correction mechanism. To investigate

this assumption, we developed a mouse-tracking analysis technique

to capture individuals’ first answers and subsequent thinking dynamics.

Across two denominator neglect task experiments, we observed that

individuals initially move the mouse cursor towards the correct answer

option in a substantial number of cases suggesting that reasoners may

not always produce an incorrect answer first. Furthermore, we observed

that, compared to low capacity reasoners, high capacity individuals

revise their first answer more frequently if it is incorrect and make

fewer changes if it is correct. However, we did not find evidence that

high capacity individuals produce correct initial answers more

frequently. Consistent with the predictions of previous decision-making

models, these results suggest that in the denominator neglect task the

capacity-normativity relationship arises after the initial response is

formulated. The present work demonstrates how the analysis of mouse

trajectories can be utilized to investigate individual differences in

decision-making and help us better apprehend the dynamics of thinking

behind decision biases.

Keywords: individual differences, process-tracing, reasoning,

heuristics and biases, denominator neglect, mouse-tracking

1 Introduction

In the simplest form of the denominator neglect task, participants are

asked to choose the larger of two ratios. The fact that individuals

often base their answer on the comparison of the numerators instead of

comparing the value of the ratios suggests that simple changes in the

way this information is presented may influence decisions (Bonner &

Newell, 2010). For example, the perceived risk of developing cancer

(Yamagishi, 1997) or the willingness to accept health-related risks

(Pinto, Martinez & Abellan, 2006) can increase if the risk

probabilities are expressed as a ratio of large numbers compared to an

equivalent ratio of small numbers. One central goal of reasoning and

decision-making research is to understand why such biases occur and

why some individuals are more susceptible to these biases than others

(Baron, 2008; Kahneman, 2011). Joining this endeavor, the current

research aims to investigate individual differences in susceptibility

to biases and the dynamics of cognitive processes underlying those

individual differences.

Individual differences in cognitive capacity1 have been shown to be a powerful

predictor of normatively correct responding in a variety of heuristics

and biases (HB) tasks. This capacity-normativity relationship has

been found in syllogistic reasoning problems (Stanovich & West, 1998;

Stanovich & West, 2008; Svedholm-Häkkinen, 2015), framing tasks

(Bruine de Bruin, Parker & Fischhoff, 2007; Frederick, 2005; Parker

& Fischhoff, 2005; Stanovich & West, 2008), base rate tasks

(Stanovich & West, 1998), belief bias (Stanovich & West, 2008) and

probability matching tasks (West & Stanovich, 2003). Similarly,

people with higher IQ and SAT scores give more correct answers in the

denominator neglect task (Kokis, Macpherson, Toplak, West &

Stanovich, 2002; Stanovich & West, 2001; Thompson & Johnson, 2014).

Kahneman and Frederick (2002) argued that more intelligent individuals

show better performance on HB tasks because they use their deliberative

processes more efficiently to override the output of the first,

incorrect heuristic response. They add that this can occur via two

possible paths. High ability reasoners may be more likely to learn the

necessary logical rules (commit fewer errors of comprehension) and/or

they may be better able to apply the learned rules in a more effective

way (commit fewer errors of application).

Stanovich and West (2008) further developed these ideas in their

framework and determined three loci from where individual differences

can arise. First, if the reasoner does not have the relevant

declarative knowledge and procedures (mindware) available to solve an

HB task, she will end up with the incorrect answer. Second, even if the

reasoner has the necessary mindware available, she has to recognize the

need of applying the appropriate strategy; otherwise, she will not

override the heuristic response. Finally, even if the reasoner has the

sufficient knowledge to solve the problem and detects the need to

override the first incorrect response, she will not come to the correct

answer if she does not have the sufficient cognitive capacity for the

required sustained inhibition and cognitive decoupling.

De Neys and Bonnefon (2013) applied a similar partitioning of the

possible causes of the individual differences in thinking biases, using

the ‘storage’, ‘monitoring’ and ‘inhibition’ labels to refer to the

different loci of individual differences (the ‘whys’). The authors

suggested an additional approach to organize the literature and

differentiated between early and late divergence between biased and

non-biased individuals (the ‘whens’). Interestingly, in their

framework, even in the case of early divergence, biased and non-biased

reasoners start to go on a different path only after the first

intuitive response has been formulated.

Evans (2007) developed two hypotheses aiming to provide explanations for

the capacity-normativity relationship. According to the

quantity hypothesis, individuals with higher cognitive ability

have a higher propensity to engage in analytic reasoning which makes

them more prone to override the first heuristic answer. In contrast,

the quality hypothesis states that better performance of

higher ability individuals arises because they are more likely to come

to the normative solution once they are engaged in analytic reasoning.

The common aspect of these approaches is that they all assume a

specific pattern that people’s decision-making process follows when

solving HB tasks: initially they will produce an incorrect answer,

which they may or may not override at a later point.2 Consequently, all

of these models assume that the capacity-normativity relationship

arises late3 in the

decision-making process. This late correction mechanism determines

whether one changes her mind from the initially produced incorrect

response.

However, recent studies using the two-response paradigm (Thompson,

Prowse Turner & Pennycook, 2011) challenged the assumption that

people always start their thinking with an incorrect response in the HB

tasks. In the two-response paradigm, people are asked to provide an

initial intuitive answer (along with other measures), after which they

are encouraged to take as much time as they need to rethink their

response to give the correct answer (for a detailed description, see

Thompson et al., 2011). Applying this paradigm to several HB tasks

(such as the denominator neglect task, the base rate task, a causal

reasoning task, and a categorical syllogism task), Thompson and Johnson

(2014) provided evidence that people start their thinking with a

correct initial response in a considerable number of cases (see, for

additional supporting results: Pennycook & Thompson, 2012; Thompson et

al., 2011). Bago and De Neys (2017) found similar results applying

time-pressure and cognitive load in the two-response paradigm which

further supports the idea that people often have a correct initial

response. Szaszi, Szollosi, Palfi and Aczel (2017) employed a thinking

aloud procedure to investigate the thinking processes in the Cognitive

Reflection Test (CRT), a popular measure showing how HB tasks can

trigger an incorrect initial answer. The authors found that in 77% of

the trials with correct responses, the respondents did not begin by

verbalizing any consideration of the intuitive response, suggesting

that they may have started their thinking already with a correct

response or with a line of thought leading to the correct response when

solving the tasks of the CRT.

Some recent data also question that the capacity-normativity

relationship in HB tasks arises from thought processes that occur after

the first response is formulated. Thompson and Johnson (2014) found

that in three of the four HB tasks investigated in their study, IQ

significantly correlated with the normativity of the first answer to a

similar extent as with the normativity of the final response,

suggesting that IQ is associated with correct first responses.

Svedholm-Hakkinen (2015) found that in contrast to the less cognitively

abled, the highly skilled reasoners did not show a sign of

belief-inhibition (longer reaction times) in the conflict version of

the belief bias syllogisms task compared to the non-conflict version of

the same task. Szaszi et al. (2017) investigated whether individuals

with higher cognitive capacity, as measured by the Berlin Numeracy Test

(Cokely, Galesic, Schulz, Ghazal & Garcia-Retamero, 2012), more often

start their thinking with a correct intuition or strategy in the CRT

tasks. Bayes factor analysis revealed that their data were too

insensitive to draw conclusions regarding this question.

There are two possible limitations of the previously described studies

investigating individuals’ first answers in HB tasks. First, as the

results are based on self-report measures, it cannot be ruled out that

in order to look more socially desirable, individuals do not report

their very first (and potentially incorrect) response, but only an

answer on which they elaborated more already. Second, a critic can

argue that the fact that participants have to provide the initial

answer in the two-response paradigm can affect the subsequent

reasoning process – even if it does not alter the final answer

compared to conditions without interruption (Thompson et al., 2011).

In the current research, we developed a mouse-tracking analysis

technique to assess individual differences in people’s decision

dynamics in HB tasks. An important advantage of this method is that it

does not rely on self-reports and that it does not interrupt people’s

decision process. In our experiments, we recorded participants’ mouse

movements in a computerized version of the denominator neglect task.

Our goal was twofold. First, we aimed to investigate the assumption that

reasoners first produce incorrect answers in HB tasks. Accordingly, we

explored the proportion of trials in which individuals moved their

mouse initially towards the correct response. Second, we investigated

why higher capacity people give more normative answers. Specifically,

we tested three explanations: Higher capacity people (1) have a higher

likelihood for initially correct answers, (2) are more likely to stay

with their initial answer when it is correct, and (3) are more likely

to change their mind when their initial answer is incorrect.

We chose the denominator neglect task to test these hypotheses, firstly,

because as a simple two choice reasoning problem, it is an ideal

candidate for mouse-tracking analysis; secondly, because previous

studies demonstrated that individual differences robustly arise in this

task (e.g., Kokis et al., 2002; Stanovich & West, 2001; Thompson &

Johnson, 2014). Our third reason was that the denominator neglect task

contains both incongruent and congruent trials which can be used to

measure the sensitivity of the mouse-cursor analysis: we expected to

find fewer correct initial response and more changes of minds in the

incongruent trials (see Bonner & Newell, 2010; Thompson & Johnson,

2014).

The current paper contains two experiments: a mouse-tracking experiment

and its replication. Since we had to make several post-hoc changes in

the analysis of Experiment 1, we replicated the study to ensure that

our findings are robust. As the methods and the analyses were identical

for both experiments, we report them conjointly.

2 Methods

2.1 Denominator neglect task

In the denominator neglect task, participants were presented with two

ratios and were asked to choose the larger one. Note that in this

simple version of the denominator neglect task, we displayed only the

ratio pairs but not pictures of trays and the description of the task

was also simplified accordingly.4 The ratio pairs

used in the current study were taken from Experiment 2 of Bonner and

Newell (2010). Every ratio pair consisted of a ‘small-ratio’ and a

‘large-ratio’. The denominator of the ‘small ratio’ was always 10

while the numerator was either 1, 2, or 3. For the ‘large ratio’, the

denominator was always 100 while the numerator changed in a way that

the value of the large ratio could differ from the smaller ratio

within the range of −9/100 and 9/100. In 27 trials, the large ratio

had a higher value (congruent trials), while in the other 27 trials, the

value of the small ratio was higher (incongruent trials).

It has been argued that, in the incongruent trials, an incorrect

heuristic response is triggered based on the comparison of the

numerators (e.g., Stanovich & West, 2001; Bonner & Newell, 2010;

Thompson & Johnson, 2014). As a result, people (incorrectly) tend to

choose the ratio with the higher numerator while neglecting the

denominator.

Note that we used both the incongruent and congruent trials to test

the sensitivity of our analysis, but used only the incongruent trials

to test our main hypotheses, since our interest in the current study

was the investigation of thinking dynamics in a task where supposedly

the first heuristic answer is incorrect.

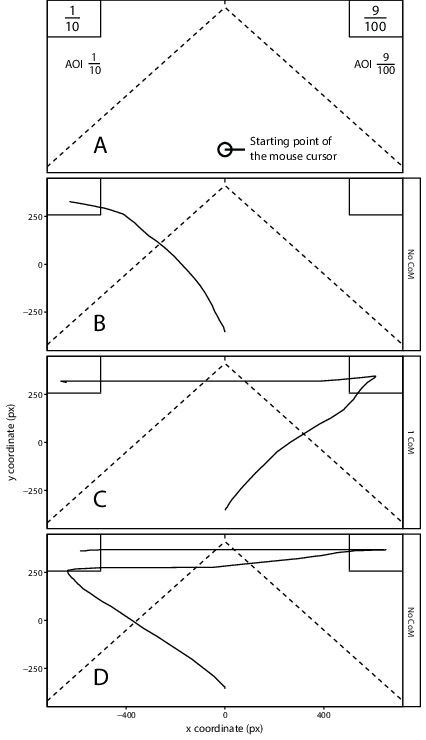

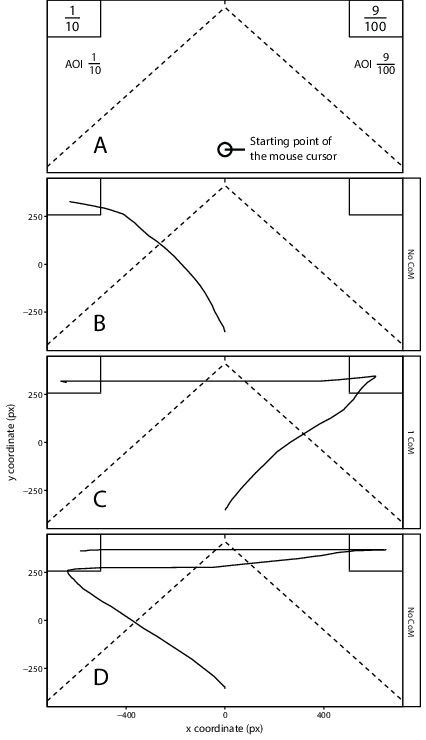

| Figure 1: Figure 1A shows an exemplary ratio pair along

with the borders of the corresponding areas of interests (AOIs) and

the starting position of the mouse cursor. Figure 1B, 1C and 1D show

three exemplary mouse trajectories. Figure 1B depicts a

case where the participant moves the mouse-cursor directly to the

left option. As the mouse trajectory enters only into the left AOI,

here we conclude that there was only one choice commitment towards

the left option and there was no Change of Mind (CoM).

Figure 1C shows a case where ultimately the left

option is chosen but the cursor was first moved into the right

AOI. Here, we conclude that there were two choice commitments, the

first commitment was to the right option which differed from the

final answer, consequently we classify this as a CoM

trial. Figure 1D illustrates a case when the individual

moves the mouse cursor first into the left AOI, then to the right

AOI and finally again to the left AOI. Here, we conclude that the

individual was first committed towards the left option, then towards

the right option before finally choosing the left option. We

categorize such trials as no CoM, since the first commitment and the

final answer were the same. |

2.2 Cognitive capacity measures

We administered an adaptive IQ test (Kovacs & Temesváry, 2016) which

applies Raven-like matrices and was adapted to the Hungarian

population.5 In contrast

to classical paper-pencil tests, the adaptive IQ test uses a response

item-bank and the items shown to each participant is determined by the

individual past performance. The procedure ends when the error range

of estimation is smaller than a pre-defined threshold. Participants

were also asked to fill out the Berlin Numeracy Test (BNT) which

measures numeracy (Cokely et al., 2012).6

2.3 Procedure

The experiments consisted of two sessions, an offline and an online

session. For the offline session, participants were invited in groups

of 15–20 to a computer test room. The computer screens had a 1440×900

px resolution and the standard mouse-sensitivity settings for

Microsoft Windows 8 Enterprise were used (medium mouse speed,

acceleration turned on). The experiments were built and run in

OpenSesame (Mathôt, Schreij & Theeuwes, 2012). The mousetrap plug-in

for OpenSesame (Kieslich & Henninger, 2017) was used to record the

x- and y-coordinates of the computer

mouse-cursor every 10 ms during the trials. At the beginning of each

experiment, participants provided informed consent and read the

following instructions: “In the experiment, you will see ratio pairs

and your task is to choose the larger value. Use the mouse cursor to

indicate your decision.” No information was provided about the

mouse-tracking aspect of the experiment. Afterwards, participants

completed four practice trials to familiarize themselves with the

task. This was followed by the presentation of 54 ratio pairs in a

randomized order for each participant. Participants had to click a

start button in the bottom center of the screen to start a new trial

(after which the mouse-cursor was automatically relocated to a

predefined start position in the bottom center of the screen). In each

trial, participants were presented with two ratios it the top right

and left corner of the computer screen (Figure 1). The left/right

position of the ratios was randomized on the trial level. Participants

had 3 seconds to make their decision in each trial.7 Aside

from the mouse movements, the accuracy and response time were recorded

in each trial. After the offline session, participants were sent an

email containing the information about the online session. Here, they

were asked to fill out an online test package containing the cognitive

capacity measures. Only participants who completed both the cognitive

capacity tests and the denominator neglect task were included in the

analysis.

2.4 Measuring dynamics of thinking using mouse-tracking

In a typical mouse-tracking paradigm, participants are asked to choose

between two spatially separated options on the screen while the

movement of their computer mouse is recorded. It is assumed that, if

the decision maker considers choosing one of the choice options, she

moves the mouse cursor towards that option (Freeman, Dale & Farmer,

2011; Koop & Johnson, 2011; Koop, 2013; Spivey, Grosjean & Knoblich,

2005; Travers, Rolison & Feeney, 2016). To assess the temporal

development of participants’ choice commitments, we developed a

mouse-tracking analysis using the areas of interest (AOI) technique

(see Palfi, Kieslich, Szaszi, Wulff & Aczel, 2018, for a detailed

description of the method and a comparison with other

methods).8 The main idea behind this technique is that one can

explore a reasoner’s first and subsequent choice commitments by

creating AOIs surrounding the choice options (see Figure 1A) and

analyzing the order in which the AOIs were visited by the mouse cursor

in each trial (for similar approaches, see Travers et al., 2016, and

Gürçay & Baron, 2017).9

In the current study, we used the reasoner’s initial commitment (i.e.,

first AOI around one of the choice options visited by the

participant’s mouse cursor) as a proxy for the participant’s first

answer. If this first commitment differed from the individual’s final

answer, we classified the trial as a Change of Mind (CoM) trial (e.g.,

in Figure 1C). Note, that to categorize a trial as a CoM trial, it was

necessary that the first and final answer differed (as is the case in

Figure 1C but not in Figure 1D). This was done as we were specifically

interested in changes between the first commitment and the final

response – and not in potential additional changes happening in

between.

2.5 Analysis

Analyses were performed using the statistical programming language R (R

Core Team, 2016). Mouse movements were processed and analyzed using the

mousetrap R package (Kieslich, Wulff, Henninger, Haslbeck &

Schulte-Mecklenbeck, 2016). In the analyses, choices and responses were

predicted in linear mixed models using the lme4 package (Bates,

Maechler, Bolker & Walker, 2015), specifying a random intercept for

each participant (the tested models are available in the Supplementary

Analysis Code). For response times, we used a linear mixed model and

p-values were obtained with the lmerTest package

(Kuznetsova, Brockhoff & Christensen, 2017); for dichotomous outcomes

(choices, correct first answers, changes of mind), we used a

generalized linear mixed model with a binomial link function.

| Table 1: Descriptive statistics of accuracy of the final and the first answer,

changes of mind, and response times in experiment 1 and 2. |

| | | Accuracy of first response (%) | Accuracy of final response (%) | Change of mind (%) | Response time (ms) |

| | | M | SD | | M | SD | | M | SD | | M | SD |

| Experiment 1 | Congruent | 73 | 44 | | 85 | 36 | | 20 | 40 | | 1479 | 495 |

| | Incongruent | 45 | 50 | | 84 | 37 | | 45 | 50 | | 1625 | 498 |

| Experiment 2 | Congruent | 69 | 46 | | 85 | 36 | | 26 | 44 | | 1567 | 477 |

| | Incongruent | 43 | 50 | | 85 | 35 | | 49 | 50 | | 1695 | 469 |

| Note. Means and standard deviations are calculated based on the

trial level values (ignoring participants).

|

2.6 Participants

Experiment 1:

Participants were recruited from a local

university subject pool in Hungary and received course credit in

exchange for participation. 109 undergraduate students provided answers

on the cognitive capacity tests and the denominator neglect task. The

participants who provided only 0 or 1 (out of 27) correct answers in

one of the conditions of the denominator neglect task (8 participants)

and those participants who obtained (for university students)

unrealistically low scores on the IQ test (<85, 4

participants) were excluded as these patterns indicated that the

participants were unmotivated to follow the instructions. Furthermore,

the trials on which participants failed to respond within the 3 second

time limit were omitted from the analyses (4% of trials). 97

participants were included in the final analyses (88% female, mean age

= 20.95 years, SD = 1.75; all Hungarian native speakers).

Experiment 2:

Participants were recruited from the same local

subject pool excluding those who participated in Experiment 1. From the

143 participants that completed the cognitive capacity measures and the

denominator neglect task, 10 and 4 participants were excluded

respectively employing the same exclusion criteria (and 4% of trials

were excluded as they exceeded the 3 seconds time limit). The remaining

129 participants were included in our final analyses (53% female, mean

age = 20.27 years, SD = 1.55; all Hungarian native speakers).

3 Results

Table 1 summarizes several aspects of participants’ responses: accuracy

of the first answer, accuracy of the final answer, CoMs, and response

times in both the congruent and in the incongruent conditions. While

the accuracy of the final answer was significantly higher in congruent

compared to incongruent trials, the difference was only small on a

descriptive level. However, participants took significantly longer to

respond in incongruent trials. The mouse-tracking method showed the

expected pattern regarding the effect of congruency: there was a

substantially lower percentage of correct first answers in incongruent

compared to congruent trials. Likewise, there were more CoMs in

incongruent compared to congruent trials. As can be seen in Table 2,

all differences were statistically significant.

| Table 2: Results of (generalized) linear mixed models for different

predicted variables in Experiment 1 and 2 with congruency as a

predictor. |

| Predicted variable | Experiment | Estimate (OR/b) | 95% CIs | Test statistic (z/t) | p |

| Accuracy of first response | 1 | 3.80 | [2.81, 5.14] | 8.67 | < .001 |

| | 2 | 3.30 | [2.62, 4.16] | 10.07 | < .001 |

| Accuracy of final response | 1 | 2.16 | [1.33, 3.54] | 3.08 | .002 |

| | 2 | 2.23 | [1.28, 3.86] | 2.84 | .004 |

| Changes of mind (CoM) | 1 | 0.29 | [0.23, 0.36] | −10.66 | < .001 |

| | 2 | 0.34 | [0.28, 0.41] | −11.26 | < .001 |

| Response time (RT) | 1 | −152.99 | [−181.78, −124.20] | −10.42 | < .001 |

| | 2 | −129.78 | [−155.67, −103.89] | −9.83 | < .001 |

| Note. The estimates represent the change in the estimate in the

congruent condition compared to the incongruent condition in a

(generalized) linear mixed model on the trial level specifying a random

intercept and random slope per participant. For RT, unstandardized

coefficient estimates (b) and t-values are

reported; for all other variables, odds Ratios (OR) and

z-values are reported.

|

3.1 Exploring the dynamics of thinking: accuracy of first

and final answers

Since our interest in the current study was the investigation of

thinking dynamics in a task where supposedly the first heuristic answer

is incorrect, in the subsequent analyses we analyzed only the

incongruent trials. Table 3 shows the number of correct and incorrect

final responses in the incongruent trials based on what the

participant’s first commitment was. As expected, in many trials,

participants started to move the mouse towards the incorrect answer

first; they mostly ended up changing their mind and choosing the

correct answer in the end. Still, several trials with an initially

incorrect response resulted in incorrect final responses. However,

there were also several trials in which an individual’s first answer was

the correct response and where this also corresponded to the final

answer. If the initial response was correct, participants changed their

mind only in a small number of cases and provided an incorrect final

response.

| Table 3: Percent of trials (in the incongruent condition) per experiment

classified based on the correctness of the initial and final response. |

| Expt. | | Correct initial response | Incorrect initial response |

| 1 | Correct final response | 42% | 42% |

| | Incorrect final response | 3% | 13% |

| 2 | Correct final response | 40% | 45% |

| | Incorrect final response | 3% | 11% |

| Table 4: Results of generalized linear mixed models using the cognitive capacity

score to predict the correctness of the initial and final response in

the incongruent condition in Experiment 1 and 2. (All models are generalized linear mixed models with a

binomial link function.) |

| Predicted variable | Expt. | OR | 95% CI | z | p |

| 21inCorrectness of final response | 1 | 1.43 | [1.13, 1.81] | 3.01 | .003 |

| | 2 | 1.58 | [1.30, 1.93] | 4.62 | < .001 |

| 21inCorrectness of initial response | 1 | 1.05 | [0.93, 1.18] | 0.80 | .424 |

| | 2 | 0.98 | [0.90, 1.07] | −0.45 | .656 |

3.2 Dynamics of the capacity-normativity relationship

To explore whether cognitive capacity predicts individual differences

in this task, we first investigated whether higher capacity people

gave more normative responses in the incongruent trials of the

denominator neglect task. We calculated composite scores from the IQ

and the BNT10 scores and used these as an

indicator for an individual’s general cognitive capacity. These composite

scores were calculated as the sum of the z-transformed IQ

and the BNT scores. Then we regressed the accuracy of the final answer

on the composite score in a generalized linear-mixed model. As

expected, the composite score predicted overall normative accuracy in

both experiments, as the odds of accurate answers increased with

increasing composite scores (Table 4).

In addition, we investigated whether the composite scores predicted the

accuracy of participants’ first commitments. The analysis revealed no

significant effect of the composite score in either of the experiments

(Table 4).

Finally, we aimed to assess whether higher capacity individuals give

more accurate final answers either because they make fewer changes when

their initial answer is correct or because they are more likely to

change their mind when their initial answer is incorrect – or both.

Accordingly, we built a generalized linear mixed model testing whether

the composite score predicted the number of CoMs when the initial

answer was correct, and another model testing the relationship of

composite score and CoMs when the initial answer was incorrect. As can

be seen in Table 5, the analyses in both experiments revealed

a significant main effect of the composite score on CoMs: higher

capacity people made more normative CoMs and less non-normative CoMs.

4 Discussion

| Table 5: Results of generalized linear mixed models using the cognitive capacity

score to predict the occurrence of a change of mind depending on the

correctness of the initial answer in the incongruent condition in

Experiment 1 and 2. (All models are generalized linear mixed models with a

binomial link function.) |

| Initial answer | Experiment | OR | 95% CI | z | p |

| Incorrect | 1 | 1.45 | [1.11, 1.90] | 2.75 | .006 |

| | 2 | 1.77 | [1.42, 2.20] | 5.06 | < .001 |

| Correct | 1 | 0.67 | [0.47, 0.95] | −2.28 | .023 |

| | 2 | 0.70 | [0.53, 0.93] | −2.43 | .015 |

In two experiments, we aimed to explore the dynamics of people’s

decision-making to better understand why some individuals are more

susceptible to biased thinking than others. We applied a novel

mouse-tracking analysis technique to track people’s first answer and

thinking dynamics in reasoning situations without interrupting the

reasoning process or relying on self-report measures. Using this

method, we investigated the assumption that reasoners initially produce

an incorrect answer in HB tasks. We observed that even in the

incongruent trials of the denominator neglect task individuals move the

mouse cursor first toward the correct response option in a substantial

number of cases. This finding provides converging evidence with the

result of recent studies using different methods (such as two response

paradigms or thinking aloud protocols; see e.g., Bago & De Neys, 2017;

Szaszi et al., 2017; Thompson & Johnson, 2014; Thompson et al., 2017)

that people sometimes produce correct initial responses in HB tasks and

that not everyone begins with a commitment to the incorrect response.

This finding suggests that models describing processes and individual

differences in HB tasks need to explain and integrate the existence of

the correct first responses. Bago and De Neys (2017) proposed that

neither the classic default-interventionist (corrective) dual process

theory nor the classic parallel dual process models can account for

this pattern and that such results are most aligned with a

hybrid-model.11 Their hybrid model suggests

that several initial, intuitive responses (correct and/or incorrect)

can be generated simultaneously, and their absolute strength will

determine which of them will be used as the first answer. If the

strength of the correct alternative is stronger, peoples’ first answer

will be correct (for an alternative hybrid model, see Pennycook,

Fugelsang & Koehler, 2015). Note, however, that we cannot

differentiate between the hybrid, default or parallel dual process

models based on our results, since we cannot test one crucial element:

which answer was generated by intuition and which by

deliberation. Future research is needed to address this issue.

Travers et al. (2016) applied a similar mouse-tracking analysis to

investigate the time-course of conflict in the CRT. In their paradigm,

4 different response options were presented to the participants and the

authors analyzed the mouse trajectories to determine the sequence in

which reasoners considered the response options. According to the model

supported by their experiment, participants move the mouse-cursor

towards the incorrect ‘heuristic’ option before choosing the correct

option. Based on this result, the authors concluded that the CRT tasks

automatically trigger a heuristic response which has to be suppressed

in order to respond correctly. One might be tempted to infer that these

results contradict our findings, but note that their results do not

imply that reasoners never start with the correct response. Similarly,

our findings do not indicate that the participants never had an

incorrect first answer. The data suggests that although in the majority

of incongruent trials individuals move the mouse cursor towards the

incorrect response, sometimes they are first committed to the correct

response.

We investigated another important aspect of individual differences in

the HB tasks: the time point at which the capacity-normativity

relationship arises. In contrast to Thompson and Johnson (2014), we

did not find evidence for the idea that the high capacity reasoners

produce more correct first answers.12 Instead, we found that differences in performance

between high and low capacity people arise after the first response is

formulated. This finding is in line with the predictions of previous

frameworks (De Neys & Bonnefon, 2013; Evans, 2007; Kahneman &

Frederick, 2002; Stanovich & West, 2008). We observed that

deliberation after the first response benefited higher capacity

people in two ways: they changed their mind more often after an

incorrect first response, and they changed their first response less

often if it was correct. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical

study showing that the latter effect also contributes to the

capacity-normativity relationship.13

Further research needs to investigate the exact role of previously

identified causal mechanisms such as differences in the storage,

monitoring ability, inhibition of the first response (De Neys &

Bonnefon, 2013), feeling of conflict (Pennycook, Fugelsang & Koehler,

2015), qualitative versus quantitative differences in deliberation

(Evans, 2007) or answer verification (Szollosi, Bago, Szaszi & Aczel,

2017) which potentially drive the advantage of these late processes.

We think that the AOI mouse-tracking analysis technique can provide an

additional way to test important questions in the reasoning literature

and has some important advantage in tracking the first answer. First,

in contrast to studies where participants are aware that the process of

their thinking is tracked, mouse-tracking is much less obtrusive and

might therefore decrease the likelihood that participants try to

deliberately hide their dynamics of thinking. This is especially

important if participants are not confident about their intuitions or

strive to appear more competent. Secondly, the AOI mouse-tracking

technique can assess the initial response without interrupting the

decision process. Therefore, mouse-tracking based methods can be

especially useful and sensitive tools to track individuals first

commitments and choice tendencies.

A key underlying assumption of the employed mouse-tracking paradigm is

that, if a choice option (i.e., response) is activated in the reasoners

mind, she will move the mouse towards the activated option.14 However, a critic might

argue that we cannot exclude unequivocally that the reasoners

deliberatively suppressed an activated heuristic answer before they

started to move their mouse cursor. Although we accept this possibility

as a limitation of our findings, we argue that our paradigm appeared to

be at least to some degree sensitive to initial responses, given

that the reasoners were more likely to first move the mouse towards the

incorrect response option in incongruent than in congruent trials.

Three more issues need to be considered in relation to our findings.

First, similar to previous research investigating the

capacity-normativity relationship, we cannot make conclusions on which

component of cognitive capacity caused the observed effects in our

study. Second, it also remains for future research to explore what

effect cognitive style has on the dynamics of thinking in HB tasks.

Finally, since previous studies suggested that HB tasks are not as

homogenous as previously thought (Aczel, Bago, Szollosi, Foldes &

Lukacs, 2015), future studies should explore how the present findings

generalize to other tasks or even to other versions of the denominator

neglect task. Although the present results indicate that more accurate

responding of higher capacity individuals in the denominator neglect

task generally arises from either the override of the first response

if it was incorrect or the less frequent change of the first response

if it was correct, it is safe to hypothesize that the model supported

in this paper is not going to work everywhere.15 In some contexts, some individuals give biased answers

because they produce quick incorrect responses, while in other cases

the biased answer is rather the results of a lack of deliberate

thinking. Future research needs to create a taxonomy and determine the

personality and task features which lead one or the other type of bias

to dominate.

In the present research, we studied how individuals differ in their

ability to provide normative responses and tested some of the key

predictions of the models describing individual differences in HB

tasks. Using a novel mouse-tracking analysis technique (based on AOIs), we

consistently found that individuals produce both correct and incorrect

first answers in the denominator neglect task. Furthermore, the

capacity-normativity relationship seemed to arise late in the

decision-making process in line with the predictions of several

decision-making models; that is, we did not find evidence that higher

capacity individuals had more correct initial answers but observed that

reasoners corrected their first answer more often if it was incorrect.

Moreover, we observed that high capacity individuals made fewer changes

after correct first answers. Our study showcases how mouse-trajectory

analysis can be utilized to investigate individual differences in

decision-making and its results can help better apprehend the

time-course of thinking and individual differences in HB tasks.

References

Aczel, B., Bago, B., Szollosi, A., Foldes, A., & Lukacs, B. (2015).

Measuring Individual Differences in Decision Biases: Methodological

Considerations. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1770.

Bago, B., & De Neys, W. (2017). Fast logic?: Examining the time course

assumption of dual process theory. Cognition, 158,

90–109.

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting

Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical

Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Baron, J. (2008). Thinking and deciding. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Bonner, C., & Newell, B. R. (2010). In conflict with ourselves? An

investigation of heuristic and analytic processes in decision making.

Memory & Cognition, 38(2), 186–196.

Bruine de Bruin, W., Parker, A. M., & Fischhoff, B. (2007). Individual

differences in adult decision-making competence. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 938–956.

Cokely, E. T., Galesic, M., Schulz, E., Ghazal, S., & Garcia-Retamero,

R. (2012). Measuring risk literacy: The Berlin numeracy test.

Judgment and Decision Making, 7(1), 25–47.

De Neys, W., & Bonnefon, J.-F. (2013). The “whys” and “whens” of

individual differences in thinking biases. Trends in Cognitive

Sciences, 17(4), 172–178.

Epstein, S., & Pacini, R. (2001). The influence of visualization on

intuitive and analytical information processing. Imagination,

Cognition and Personality, 20(3), 195–216

Evans, J. S. B. (2007). On the resolution of conflict in dual process

theories of reasoning. Thinking & Reasoning, 13(4),

321–339.

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making.

The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 25–42.

Freeman, J. B. (2014). Abrupt category shifts during real-time person

perception. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21(1),

85-92.

Freeman, J., Dale, R., & Farmer, T. (2011). Hand in motion reveals mind

in motion. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 59.

Gürçay, B., & Baron, J. (2017). Challenges for the sequential

two-system model of moral judgement. Thinking & Reasoning, 23(1), 49–80.

Hehman, E., Stolier, R. M., & Freeman, J. B. (2015). Advanced

mouse-tracking analytic techniques for enhancing psychological science.

Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 18(3),

384–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430214538325

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York, USA:

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., & Frederick, S. (2002). Representativeness revisited:

Attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In T. Gilovich, D.

Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics of Intuitive

Judgment: Extensions and Applications (pp. 49–81). New York, NY, USA:

Cambridge University Press.

Kieslich, P. J., & Henninger, F. (2017). Mousetrap: An integrated,

open-source mouse-tracking package. Behavior Research Methods, 49(5),

1652–1667. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0900-z.

Kieslich, P. J., Wulff, D. U., Henninger, F., Haslbeck, J. M. B., &

Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M. (2016). Mousetrap: An R package for processing

and analyzing mouse-tracking data.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.596640

Kokis, J. V., Macpherson, R., Toplak, M. E., West, R. F., & Stanovich,

K. E. (2002). Heuristic and analytic processing: Age trends and

associations with cognitive ability and cognitive styles.

Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 83(1),

26–52.

Koop, G. J. (2013). An assessment of the temporal dynamics of moral

decisions. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(5), 527–539.

Koop, G. J., & Johnson, J. G. (2011). Response dynamics: A new window

on the decision process. Judgment and Decision Making, 6(8),

750–758.

Kovacs, K., & Temesvari, E. (2016). Számítógépes, adaptív IQ-mérés: Egy

gyakorlati példa. [Computerized, adaptive IQ measurement: An example

from Hungary]. Magyar Pszichológiai Szemle, 71(1),

143–163.

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017).

lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal

of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26.

Mathôt, S., Schreij, D., & Theeuwes, J. (2012). OpenSesame: An

open-source, graphical experiment builder for the social sciences.

Behavior Research Methods, 44(2), 314–324.

Parker, A. M., & Fischhoff, B. (2005). Decision-making competence:

External validation through an individual-differences approach.

Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 18(1), 1–27.

Palfi, B., Kieslich, P. J., Szaszi, B., Wulff, D. U., & Aczel, B.

(2018) Detecting changes of mind through mouse-tracking.

Manuscript in preparation.

Pennycook, G., & Thompson, V. A. (2012). Reasoning with base rates is

routine, relatively effortless, and context dependent.

Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(3), 528–534.

Pennycook, G., Fugelsang, J. A., & Koehler, D. J. (2015). What makes us

think? A three-stage dual-process model of analytic engagement.

Cognitive Psychology, 80, 34–72.

Pinto-Prades, J. L., Martinez-Perez, J. E., & Abellán-Perpiñán, J. M.

(2006). The Influence of the Denominator neglect Phenomenon on the

Elicitation of Health States Utilities. Judgment and Decision

Making, 1(2), 118–133.

R Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for

statistical computing. Vienna,

Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

https://www.R-project.org/.

Scherbaum, S., & Kieslich, P. J. (in press). Stuck at the starting

line: How the starting procedure influences mouse-tracking

data. Behavior Research Methods.

Spivey, M. J., Grosjean, M., & Knoblich, G. (2005). Continuous

attraction toward phonological competitors. Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,

102(29), 10393–10398.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (1998). Individual differences in

rational thought. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General,

127(2), 161–188.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (1998). Who uses base rates and P

(D/∼ H)? An analysis of individual differences. Memory

& Cognition, 26(1), 161–179.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2001). Individual differences in

reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioral

and Brain Sciences, 23(5), 645–665.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2008). On the relative independence of

thinking biases and cognitive ability. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 94(4), 672–695.

Svedholm-Häkkinen, A. M. (2015). Highly reflective reasoners show no

signs of belief inhibition. Acta Psychologica, 154,

69–76.

Szaszi, B., Szollosi, A., Palfi, B., & Aczel, B. (2017). The cognitive

reflection test revisited: exploring the ways individuals solve the

test. Thinking & Reasoning, 23(3), 207–234.

Szollosi, A., Bago, B., Szaszi, B., & Aczel, B. (2017). Exploring the

determinants of confidence in the bat-and-ball problem. Acta

Psychologica, 180, 1–7.

Thompson, V. A., & Johnson, S. C. (2014). Conflict, metacognition, and

analytic thinking. Thinking & Reasoning, 20(2),

215–244.

Thompson, V. A., Pennycook, G., Trippas, D., & Evans, J. S. G. (2017).

Do smart people have better intuitions? Unpublished

manuscript.

Thompson, V. A., Prowse Turner, J. A., & Pennycook, G. (2011).

Intuition, reason, and metacognition. Cognitive Psychology,

63(3), 107–140.

Travers, E., Rolison, J. J., & Feeney, A. (2016). The Time Course of

Conflict on the Cognitive Reflection Test. Cognition, 150,

109-118.

West, R. F., & Stanovich, K. E. (2003). Is probability matching smart?

Associations between probabilistic choices and cognitive ability.

Memory & Cognition, 31(2), 243–251.

Yamagishi, K. (1997). When a 12.86% mortality is more dangerous than

24.14%: Implications for Risk Communication. Applied Cognitive

Psychology, 11, 495–506.

This document was translated from LATEX by

HEVEA.