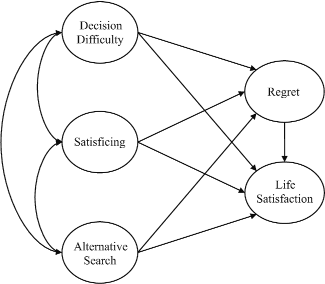

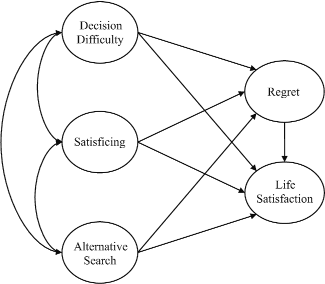

| Figure 1: Conceptual model that shows the hypothesized relationships of the study. |

Judgment and Decision Making, Vol. 9, No. 5, September 2014, pp. 500-509

The price of gaining: maximization in decision-making, regret and life satisfactionEmilio Moyano-Díaz* Agustín Martínez-Molina# Fernando P. Ponce# |

Maximizers attempt to find the best solution in decision-making, while satisficers feel comfortable with a good enough solution. Recent results pointed out some critical aspects of this decision-making approach and some concerns about its measurement and dimensional structure. In addition to the analysis of these aspects, we tested the possible mediational role of regret in this psychological process. The Maximization Inventory (MI; satisficing, decision difficulty, and alternative search), regret, and Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) were translated and adapted to Spanish in order to answer these issues with a Chilean sample. Validity and reliability analysis of the MI reports that only two dimensions of the MI have enough dimensional support (decision difficulty, alternative search). The tested structural model shows good fit of partial mediation effect of regret between decision difficulty and SWLS. At the same time, alternative search has a positive relation with SWLS. These results suggest that Regret becomes crucial for prescribing behavior to decision makers.

Keywords: maximization, decision making, regret; life satisfaction.

An important contribution to the study of decision-making process is the work carried out by Schwartz, Ward, Monterosso, Lyubomirski, White and Lehman (2002) based on the economic theory of Simon (1955 and 1956) and his observations about the limitations for decision-making under a rational choice approach. Schwartz et al. (2002), starting from Simon’s work, pointed out that the purpose of maximizing choice among options is almost always unrealizable in real life because of environment limitations and information, as well as its processing by people.

When those who should decide are satisficers (rather than maximizers), their aim is to obtain simple satisfaction and therefore they would proceed by estimating the degree of satisfaction that different objects of consumption would provide, thus establishing a degree of acceptability. Satisficers do not look for an ideal or optimal choice, but only for a good enough choice. Those who proceeded this way would experience positive emotions or subjective well-being as a result (Schwartz et al., 2002; Turner, Rim, Betz, & Nygren, 2012).

Consumers in capitalist societies have many alternatives to choose from and according to Schwartz (2000) this could adversely affect their well-being. While we make a decision between these alternatives, maximization may play a causal role on our unhappiness. The “paradox of maximization” (or choice) is that, while theoretically everyone prefers to have more choices than less to choose from, empirical evidence indicates that increases in the number of options often have negative effects on perceived well-being. Those who spend energy, time or money to seek alternative paths may experience dissatisfaction or regret later. It still remains unclear why these negative consequences occur. Research on the effect of “too much choice” or “choice-overload” has reported inconsistent results (Fasolo, McClelland & Todd, 2007; Scheibehenne, Greifeneder & Todd, 2010).

Schwartz et al. (2002) presented a four-factor solution of their original maximization scale (MS) after conducting various Principal Component Analysis and an item-total correlation criterion to purify the measures. The analysis confirmed the dimension of regret (5 items) and revealed other subcategories of maximizing (13 items) that supported the multidimensional nature of the construct. Results regarding the relationship between maximization, information search and social comparison in purchasing decisions, as well as on the subsequent satisfaction derived from such decision, were also reported. They analyzed the possible causal role of regret in mediating between maximizing and dissatisfaction. They found positive correlations between maximization and regret, perfectionism and depression, and negative correlations with happiness and optimism as well as life satisfaction and self-esteem. Maximizers engage in social comparison more than satisficers, experienced more regret and less happiness because of their decisions, and were more susceptible to regret.

Since these initial studies, maximizing tendency has become a central concept in decision-making theory and has received a lot of theoretical, methodological and empirical attention (Chowdhury, et al., 2009; Hackley, 2006; Iyengar, et al., 2006; Morrin, et al., 2008; Moyano-Díaz, Cornejo, Carreño & Muñoz, 2013; Nenkov, et al., 2008; Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007).

However, Highouse and Diab (2006) and especially Diab, Gillespie and Highouse (2008), have questioned MS for not complying with psychometric acceptable standards, questioning its validity or predictive association between maximization and unhappiness or regret. Conceptually, they argue that if maximization is a trait or an overall tendency to pursue the best option, there are items in MS that appear to be divergent from this definition (e.g., difficulty writing letters to friends, fantasizing about living a different life, etc.).

Diab et al. (2008) constructed a new instrument—The Maximizing Tendency Scale (MTS)—to measure maximazing tendency, understood as the identification of the optimal alternative. They related this measurement with MS and measurements of indecision, avoidance, regret, neuroticism and life satisfaction measures in addition to criterion-based dilemmas and behavior reports on spent resources for obtaining more information before making a decision. The MTS had higher Cronbach’s α (.80) than MS (.68), a significantly lower correlated with Regret (r = .27, vs. r = .45), and no correlation with indecision, avoidance, neuroticism or life satisfaction. The authors concluded that, while maximizers are more likely to experience regret, they are about as happy as satisficers, and don’t have a greater likelihood of being indecisive, avoidant or neurotic than satisficers. The MTS appeared to have better psychometric properties than the MS, and the authors argue that the interpretation that the maximizers are unhappy may be due to a weak or poor measure of the concept.

Other authors have also criticized the MS. A factor analysis conducted by Nenkov et al. (2008) has shown the same three original factors, search of alternatives, difficulty to decide and high standards. Analysis of the psychometric properties of MS showed reasonable internal consistency and construct validity, but the authors concluded that given the significant variation in the reliability and validity coefficients between the samples used in the study of MTS, the psychometric properties are unsatisfactory.

Rim, Turner, Betz and Nygren (2011) deepened the analysis using factor analysis, Item Response Theory (IRT) and experimental manipulation of the MS and MTS scales. They found that MS actually consists of three factors as originally planned, but only the first two—alternative search and decision difficulty—have negative correlations with well-being indexes. The third factor—high standards—correlates positively with the MTS and with measures of well-being: optimism, happiness and proper functioning (self-esteem and self-efficacy). Alternative search and decision difficulty were also related to the regret-based decision making style. High standards and MTS are related with a style of analytical or rational decision, while the other two factors are related to a decision style based on regret and procrastination. The application of IRT showed some weaknesses in both scales. Rim et al. argued that alternative search and decision difficulty should define maximization, while high standards and MTS should not.

Consistently with the reported results and criticisms of the MS (Diab et al., 2008), Turner, et al. (2012) further criticized and distilled the concept of maximization. They built The Maximization Inventory (MI) of 34 items divided into three subscales: decision difficulty (12 items), alternative search (12) and satisficing (10). The elimination of the high standards sub-scale is consistent with the earlier criticism that argues such sub-scale is not consistent with the definition of maximization. Moreover its replacement by a satisficing scale related to maximization considers that this last dimension, according to these authors, would be an entirely different dimension of maximization that is positively correlated with positive adaptation, while the other two sub-scales of maximization (difficulty in decision-making and search for alternatives) are correlated with decisional unproductive behavior.

The so defined and measured maximization appears negatively related to adaptive decision styles and well-being indexes (Turner et al., 2012). Internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha obtained for the MI was .89 for difficulty in decision-making, .82 for research alternatives and .72 for satisficing. Despite the psychometric progress recorded, the question still remains whether maximization is a search strategy or a goal and particularly, as Turner et al. (2012) proposed, if the dimension of maximization includes or remains independent from the satisficing dimension.

Moreover, the regret variable studied as the effect of decision by maximizing has been measured by Schwartz et al. (2002) and Moyano-Díaz et al. (2013). Regret is an emotion of high importance in psychic life, and among the most frequently experienced negative emotions (Saffrey & Roese, 2008). Regret is not traditionally considered a basic emotion, and it is nowadays defined as an emotion that can be experienced when a situation is realized or imagined as more beneficial had it been decided differently (Zeelenberg & Pieters 2007).

Regret is not only an emotional reaction against bad consequences, it also seems to be a powerful “drive” of behavior, that is, something can be decided looking to avoid potential regrets. Schwartz et al. (2002) found that maximizers are more likely to make social comparisons and are more affected by them. They felt less happiness and reported greater regrets with their decisions than the satisficers. Maximizers are willing to spend a great deal of energy to find the optimal option, to search about many possible alternatives, analyzing and comparing them, i.e., using rational-analytical style. Maximizers also engage in more post-decision processing than satisficers, including as we said, counterfactual thinking and social comparison, which suggests a continuing lack of confidence in their decisions. In contrast, satisficers proceed more quickly (perhaps heuristic or intuitive; Gigerenzer & Gaissmeier, 2011; Nygren & White, 2002) and decide to opt for a good enough option, with which they are happy. According to Polman (2010) maximizers get better jobs, but also experience more regret over their decisions.

Figure 1: Conceptual model that shows the hypothesized relationships of the study.

The present research examines the relationship between maximization, regret, and life satisfaction. We ask whether the relation between maximization and life satisfaction is mediated by regret. Schwartz et al. (2002) have also suggested that the regret may play a mediational role in the relationship and tendency between maximization and happiness. We used translated the Maximization Inventory (MI, Turner et al., 2012) into Spanish. It includes an independent measure of satisficing, which explains its greater length (34 items) than the brief MTS (6 items). It has three dimensions: difficulty of decision and search for alternatives—twelve items each—and satisficing with 10 items. Additionally, its three-factor structure is subjected to verification here. We will use decision difficulty, alternative search and satisficing as explanatory variables and regret and life satisfaction as outer variables. And we also test the effect of regret has a possible mediator between the maximization dimensions and life satisfaction (Figure 1). Our study does not include high standards and thus leaves open the role of this dimension as a determinant of regre and life satisfaction.

The study sample was comprised by 300 university undergraduates (190 females, 63.3% and 110 males, 36.7%), of the University of Talca (Chile) who participated voluntarily after receiving an institutional college email. Mean age was 22.2 (SD = 2.1). There were no missing data in this study.

Table 1: Items of the Maximization Inventory Spanish version (translated and adapted from Turner, Rim, Betz, & Nygren, 2012); retrieved from http://journal.sjdm.org/11/11914/jdm11914.html.

Satisficing items (Satisfacciendo) 1 Por lo general trato de encontrar un par de buenas opciones y entonces elegir entre ellas. 2 En algún momento necesitas decidir acerca de las cosas. 3 En la vida trato de sacar el máximo partido de cualquier camino que tomo. 4 Generalmente en una situación de decisión hay varias buenas opciones. 5 Trato de obtener toda la información posible antes de tomar una decisión, pero después sigo adelante y lo hago. 6 Pueden suceder cosas buenas, incluso cuando al principio las cosas no van bien. 7 No puedo saberlo todo antes de tomar una decisión. 8 Todas las decisiones tienen pros y contras. 9 Sé que puedo empezar de nuevo si cometo un error. 10 Acepto que la vida a menudo tiene incertidumbre. Decision dificulty items (Dificultad de Decisión) 11 Por lo general me cuesta tomar decisiones simples. 12 Normalmente me preocupa tomar una decisión equivocada. 13 A menudo me pregunto por qué las decisiones no pueden ser más fáciles. 14 A menudo retraso una decisión difícil hasta la fecha límite. 15 A menudo experimento remordimientos por haber comprado algo que no me convencía. 16 A menudo pienso cambiar de opinión después de que ya he tomado mi decisión. 17 La parte más difícil de tomar una decisión es saber que tendré que dejar atrás lo que no elegí. 18 A menudo cambio de opinión varias veces antes de tomar una decisión. 19 Es difícil para mí elegir entre dos buenas alternativas. 20 A veces retraso una decisión, aún cuando ya sé la decisión que finalmente tomaré. 21 A menudo me encuentro ante decisiones difíciles. 22 No me cuesta tomar decisiones. Alternative search items (Búsqueda de Alternativas) 23 No puedo decidir sin haber considerado cuidadosamente todas mis opciones. 24 Dedico tiempo para leer todo el menú cuando ceno fuera. 25 Continuaré con la compra de algo hasta que cumpla todos mis criterios. 26 Por lo general continúo la búsqueda de lo que quiero comprar hasta que satisface mis expectativas. 27 Cuando voy de compras, tengo la intención de pasar mucho tiempo buscando algo. 28 Cuando voy de compras y no encuentro exactamente lo que quiero, continúo buscándolo. 29 Voy a muchas tiendas antes de encontrar lo que quiero. 30 Cuando voy a comprar algo, no me importa pasar varias horas buscándolo. 31 Me tomo el tiempo necesario para considerar todas las alternativas antes de tomar una decisión. 32 Cuando veo algo que quiero, siempre intento conseguirlo al mejor precio antes de comprarlo. 33 Si una tienda no tiene exactamente lo que quiero comprar, entonces voy a otro lugar. 34 Yo no tomaré una decisión sino hasta sentirme cómodo con el procedimiento.

Measure were translated and adapted into Spanish according to the International Test Commission Guidelines (International Test Commission, 2010; Hambleton, 1994).

The Maximization Inventory is presented in Table 1 (MI; Turner et al., 2012). It measures three dimensions with 34 items: decision difficulty (12 items), alternative search (12 items) and satisficing (10 items). Responses were obtained on a 5-point scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5).

Table 2: Items of the Regret Spanish version (translated and adapted from Schwartz, Ward, Monterosso, Lyubomirsky, White, & Lehman, 2002); retrieved from http://www.sjdm.org/dmidi/Regret_Scale.html.

1 Cuando tomo una decisión, no miro atrás. 2 Cada vez que tomo una decisión, tengo curiosidad por saber lo que hubiera pasado si hubiera tomado una decisión diferente. 3 Cada vez que tomo una decisión, trato de obtener información acerca de cómo resultarían las otras alternativas. 4 Si tomo una decisión y resulta acertada, todavía siento una especie de fracaso si me entero de que otra opción habría resultado mejor. 5 Cuando pienso acerca de lo que estoy haciendo en mi vida, a menudo evalúo las oportunidades que he dejado pasar.

Despite claims that this instrument has better psychometric properties than previous instruments (e.g., α of .80), there are some inconsistencies between the items and the concept of maximization for which they were built (Giacopelli, et al., 2013; Weinhardt, et al., 2012), as well as conflicting results for predicting Life Satisfaction (Oishi, et al., 2014).

Regret was measured by the 5-item scale measure of Schwartz et al. (2002; see Table 2). Responses were obtained on a 5-point scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5). The reported reliability index (Cronbach α ) by these authors and other studies was from .67 to .71 (Moyano-Díaz, et al., 2013).

Finally, Life Satisfaction was measured by the SWLS scale of Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin (1985; see Table 3), one of the most frequently used measures for global assessment of life satisfaction (rather than specific domains of this construct; Pavot & Diener, 1993). The response scale consists of 5 levels (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree). The item-total correlation indices for reliability support reported by Diener, et al. (1985) ranged from .61 to .81, and the Chilean version had an α .87 and test-retest reliability of .82 (Moyano-Díaz, 2010). Appendix A shows the English version of the items.

Table 3: Items of the Life Satisfaction (Satisfacción vital) Spanish version (translated and adapted from Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin (1985), in Moyano-Díaz, 2010); see Appendix A for the English version of the scale.

1 2 3 4 5

Students received $2,000 CLP after completing a set of computerized tests, using a Web-based interface. The system collected sex, age and id variables (last one only for the payment purposes of the study). The sample of 300 participants completed the study in the computerized classrooms of the Department of Psychology. The computerized system initially displayed the informed consent document. The Maximization Inventory was shown then, and it took 5 min and 24 s on average to be completed. Regret items were then presented, with an average time of 58 s. Finally, the life satisfaction scale was completed with an average of 35 s.

Table 4: Parallels analysis, explained variance, adequacy of the analysis and fit index.

Satisficing Decision difficulty Alternative search Regret Life satisfation Number of items 10 12 12 5 5 Advised number of dimensions 2 1 1 1 1 Proportion of variance .26 .38 .46 .45 .64 GFI .96 .98 .98 .99 1.00 Bartlett’s statistic (df) 325.4(55)* 864.4 (55)* 1144.8(55)* 241.8 (10)* 576.0 (10)* KMO .698 .844 .863 .738 .841 RMSR .075 .070 .075 .054 .035 KMO = Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index; GFI = Goodness of fit index; RMSR = Root mean square of residuals. * p <0.001.

The number of factors in each scale was determined with the parallel analysis technique (Horn, 1965), which is one of the most effective ways to determine data dimensionality (Garrido, Abad & Ponsoda, 2013; Velicer, Eaton & Fava, 2000). This factor analyses employed an unweighted least-squares estimator (Unkel & Trendafilov, 2010). We used an oblique rotation, considering that the dimensions have a moderate relationship (direct oblimin, delta = 0; salient larger values > 0.30). Table 4 shows the recommended number of dimensions based on the parallel analysis, their explained proportion of variance, their Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and Barlett’s and KMO tests for the adequacy of the analysis.

Table 5: Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations and reliability coefficients (** p < 0.01 level, 2-tailed).

Satisficing Decision Difficulty -.05 Alternative search .29** .26** Regret .01 .57** .24** Life satisfaction .03 -.27** .08 -.21** MEAN 16.5 37.6 44.0 13.0 18.1 SD 2.0 7.7 6.9 2.9 3.6 Skewness -1.3 0.2 -0.3 -0.1 -0.7 Kurtosis 6.3 -0.5 0.6 -0.7 0.9 Cronbach’s α .64 .85 .85 .69 .84 McDonald’s ω .71 .84 .88 .70 .86

Except for the Satisficing scale that presented two dimensions and poor fit values, the other measures in general presented enough unidimensional support to conduct the rest of analysis (RMSR < 0.058, GFI > .95, KMO > .8; Cerny & Kaiser, 1977; Dziuban & Shirkey, 1974; Kaiser, 1970; Kelley, 1935).

Parallel analysis advised two factors rather than one on satisfying scale. On the one hand F1 by items 1, 2, 3 and 5 with real-data eigenvalues over random, and factor loadings > 0.4, and on the other, F2 by items 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 with the same pattern of loadings. The item 4 had an eigenvalue < 0.40 in the two suggested factors. The composed factor by items 1, 2, 3 and 5 had reported better-fit results than the other (KMO = .699; Barlett(55) = 325.4 p ≤ .001; GFI = 1.00, and RMSR = .027). For further analysis of this study only F1 items were considered for the Satisficing factor.

Table 5 shows descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix for the dimensions of this study. Also Table 3 shows two reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω). Descriptive statistics and reliability analyses were calculated with SPSS 20 and Factor 9.2 software (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006).

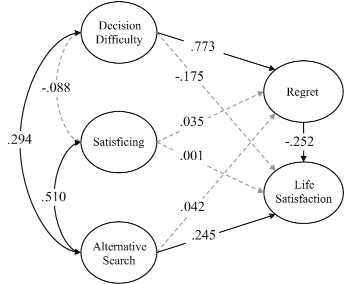

Figure 2: Estimated multiple linear regression model testing the full mediation effect of regret between the maximization dimensions and life satisfaction.

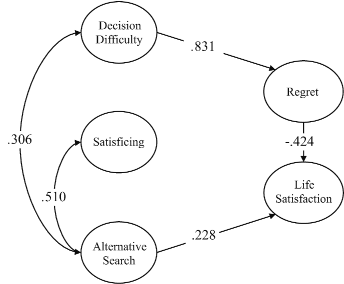

Figure 3: Partial mediation model in which regret is involved in the relationships between decision difficulty and life satisfaction and between alternative search and life satisfaction.

Because of the ordinal nature of data, the factorial analysis was based on polichoric correlations using the WLSMV estimator (Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance Adjusted) available in Mplus7 software. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were used as goodness of fit indices. Cut-off point recommendations of Schreiber, Stage, King, Nora, and Barlow (2005) were followed for goodness of fit indices interpretation (CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA < 0.06).

The models represented in Figures 2 and 3 test a full mediation effect of regret between the maximization dimensions and life satisfaction. The first estimated model reports an appropriate setting of good fit indices according to the mentioned criteria (χ 2(655) = 1351.86, p < .000, χ 2/df = 2.06, RMSEA = .060, CFI = .885, TLI = .877, R2Regret= .617, R2Life Satisfaction= .163).

Following these outcomes the model in Figure 3 is based only on previous significant relationships between measured dimensions of this study. The model shows a good fit of partial mediation effect in which regret is involved in the relationships between decision difficulty and life satisfaction (χ 2(523) = 1339.97, p < .000, χ 2/df = 2.56, RMSEA = .063, CFI = .896, TLI = .889, R2Regret= .692, R2Life Satisfaction= .183).1 As shown in Figure 2, not all maximizing components have significant relationships between them. The satisficing factor was significantly related only to alternative search. There was no second order factor convergence of the maximization model (maximization by decision difficulty, satisficing and alternative search; 1000 iterations exceeded with WLSMV estimator in CFA).

Decision difficulty and alternative search were positively related to each other (r = .31; see Figure 3), yet these factors were respectively related to regret and life satisfaction (rDecision difficulty-Regret =.83; rAlternative search-Life satisfaction = .23). The relationship between life satisfaction and regret was negative as expected (r = −.43), and the magnitude of this relation suggests a partial mediation effect between decision difficulty and life satisfaction with no other significant relationships (compared to r = −.25, see Figure 2). Decision difficulty was highly related to regret (69% of explained variance), and at the same time regret explains slightly life satisfaction (18% of explained variance).

Maximization, as a central theoretical concept in decision-making, has led to various controversies. First, corresponding to its structure, originally designed as three-dimensional, but Turner, et al. (2012) replaced one of its dimensions, high standards, with another one called satisficing, in a new instrument, The Maximization Inventory (MI), which was used here. However, the satisficing sub-dimension lacks relevant relations in the models proposed here. The only significant relationship of this dimension is with alternative search (r = .51). Our results lead us to question this dimension’s incremental validity, since the content of some of its items meaningfully overlap with the two other dimensions (e.g., the 1 item of satisficing “I usually try to find a couple of good options and then choose between them” and item 33 of alternative search, “If a store doesn’t have exactly what I’m shopping for, then I will go somewhere else” with r1–33 = .39). Additionally, the satisficing subscale of MI appears to have low reliability also following the trend of previous studies (Turner, et al., 2012). The empirical support for the unidimensionality of satisficing is limited and perhaps the problem may be in the scale items and not in the appropriateness of the concept for increasing the content validity of measures of maximization.

Our results suggest a need for a deeper review of the definition of the construct called satisficing as one independent from maximization, as well as its relationship with emotional effects concerning to the Regret Scale. The two dimensions used here that clearly seem to constitute the concept of maximization-decision-making (decision difficulty and alternative search), though proven to be adequately reliable, can still be improved with new items to increase the explained variance of the construct, which still is not particularly high. Considering the reported data in this study, there is a very important and negative relationship between decision difficulty and regret. Also, decision difficulty and alternative search dimensions had a direct and positive (although small) relationship. Both results converge with Turner et al. (2012). From a conceptual point of view, future research should address the role of high standards as a maximizing dimension. The present paper concerns only two of the three original dimensions, yet indicates that they work in different ways.

The analysis conducted here confirmed a partial mediation effect between the maximization and life satisfaction dimensions through the regret variable. This effect manifests itself only from the dimension of difficulty in decision-making and however not from alternative search. Regarding the latter, apparently having more alternatives from which to choose and decide is psychologically rewarding per se, either by stimulus novelty, satisfying curiosity, need for cognition, and sense of freedom or other mechanisms. However, it is reasonable to conjecture that the relationship can be quadratic, i.e., that from a certain number, novelty or variety of alternatives the decisional context may become overloaded. This “too much choice effect” of “choice overload” has been presented as a possible hypothesis of the negative consequences caused by the high number of available alternatives (Scheibehenne et al., 2010), even with possible short-term emotional negative effects (e.g., anxiety, tension, regret, etc.). The lack of knowledge we have about what is the “gold number” of choices during the decision making process constitute an excellent challenge for further research. Additionally, future studies on maximization should clarify the mixed or inconsistent “positive and negative” outcomes (Polman, 2010; Scheibehenne et al., 2010). The negative relationship between life satisfaction and regret may be confirmed, and may consider the emotional consequences as mediators or moderators related to the process of decision making.

Indeed, our results concur with Purvis, Howell and Iyer’s (2011) research where there is a high relationship between maximization and regret through decision difficulty and alternative search is positively related to life satisfaction. Decision difficulty is the factor that contributes most to regret.

What should be done to reduce or avoid the effects of regret for maximizers in their decision-making? Based on the results, it is useful to educate and create awareness among those who consider regret as an inevitable component or at least of high probability when taking part in a decision-making process, in such a way that one who decides must include “no price, no gain” among their costs. In this case, educating for acceptance of regret and remorse as part of the decision-making process (Bell, 1982) “a sense of loss, or regret… The decision maker who is prepared to trade off financial return… By explicitly incorporating regret, expected utility theory not only becomes a better descriptive predictor but also may become a more convincing guide for prescribing behavior to decision makers.” Regret therefore, should not be categorized as a dimension or effect only, but should be included as part of the decision-making process and then integrated within a decision-making model. When one who decides gets to understand and accept regret as a cost of the process, and perhaps also as a consequence in decision-making, then perhaps it is possible that eventual negative emotional effects could be mitigated.

Another way to lessen the regret and increase a likelihood of experiencing positive emotional states when making a decision according to Dar-Nimrod, Rawn, Lehman, and Schwartz (2009), is learning to shorten the decision-making process to reduce the search for alternatives as well as to increase the thinking based on the positive aspects of what we have chosen while decreasing attention on the alternatives and their possible effects. So, more specifically, it is increasing the perceived benefit of the chosen option and reducing the perceived benefit of rejected options (Brehm, 1956; Sparks, et al., 2012). Furthermore, a distinction could be made between two processes: regret (with a negative meaning) and rumination (pondering over, with a dual valence of positive and negative meaning). Although it has been shown that regret is positively associated with depression and anxiety, other studies had also found a positive relation between rumination and emotional improvement (Páez, et al., 2013; Da Costa, Páez, Oriol, & Unzueta, 2014). In this sense it is useful to also distinguish between voluntary-involuntary and negative-positive rumination. Positive rumination, voluntarily reflecting on the positives, may be another strategy that endorses positive affectivity during or after a decision making process (Larsen & Prizmic, 2004).

Bell, D. E. (1982). Regret in decision making under uncertainty. Operations Research, 30, 961–981. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.30.5.961.

Brehm, J. W. (1956). Postdecision changes in the desirability of alternatives. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52, 384–389.

Butts, C. T. (2012). yacca: Yet Another Canonical Correlation Analysis Package. R package version 1.1. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=yacca.

Cerny, C. A., & Kaiser, H. F. (1977). A study of a measure of sampling adequacy for factor-analytic correlation matrices. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 12(1), 43–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr1201\_3.

Chowdhury, T. G., Ratneshwar, S., & Mohanty, P. (2009). The time-harried shopper: Exploring the differences between maximizers and satisficers. Marketing Letters, 20, 155–167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11002-008-9063-0.

Da Costa, S., Páez, D., Oriol, X., & Unzueta, C. (2014). Regulación de la afectividad en el ámbito laboral: validez de las escalas de heteroregulación EROS y EIM. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 30, 13–22.

Dar-Nimrod, I., Rawn, C., Lehman, D., & Schwartz, B. (2009). The maximization paradox: The costs of seeking alternatives. Personality and Individual Differences. 46, 631–635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.007.

Diab, D., Gillespie, M., & Highhouse, S. (2008). Are maximizers really unhappy? The measurement of maximizing tendency. Judgment and Decision Making, 3, 364–370.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901\_13.

Dziuban, C. D., & Shirkey, E. C. (1974). When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Psychological Bulletin, 81, 358–361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0036316.

Fasolo, B., McClelland, G. H., & Todd, P. M. (2007). Escaping the tiranny of choice: When fewer attributes make choice easier. Marketing Theory, 7(1), 13–26.

Garrido, L. E., Abad, F. J., & Ponsoda, V. (2013). A new look at Horn’s parallel analysis with ordinal variables. Psychological Methods, 18, 435–453. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0030005.

Giacopelli, N. M., Simpson, K. M., Dalal, R. S., Randolph, K. L., & Holland, S. J. (2013). Maximizing as a predictor of job satisfaction and performance: A tale of three scales. Judgment & Decision Making, 8, 448–469.

Gigerenzer, G., & Gaissmaier, W. (2011). Heuristic decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 451–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145346.

Hackley, S. (2006). Focus your negotiations on what really matters. Negotiation, 9–11.

Hambleton, R. (1994). Guidelines for adapting educational and psychological tests: A progress report. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 10, 229–244.

Highhouse, S., & Diab, D. (2006). Who are these maximizers? Presented at the 27th Annual Conference of the Society for Judgement and Decision Making, Houston, TX.

Horn, J. L. (1965). A Rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179–185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02289447.

International Test Commission (2010). International Test Commission Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests. http://www.intestcom.org.

Iyengar, S. S., Wells, R. E., & Schwartz, B. (2006). Doing better but feeling worse: Looking for the “best” job undermines satisfaction. Psychological Science, 17, 143–150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01677.x.

Kaiser, H. F. (1970). A second generation Little Jiffy. Psychometrika, 35, 401–415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02291817.

Kelley, T. L. (1935). Essential traits of mental life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Larsen, R. J. & Prizmić, Z. (2004). Affect regulation. En: R. Baumeister y K. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation research (pp. 40–60). Nueva York: Guilford.

Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Ferrando, P. J. (2006). FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behavioral Research Methods, Instruments and Computers, 38, 88–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BF03192753.

Morrin, M., Inman, J. J., Broniarczyk, S. M., & Broussard, J. (2008). Decomposing the 1/n heuristic: The moderating effects of assortment size and decision style. Working paper, Rutgers University, Camden, NJ.

Moyano-Díaz, E. (2010). Exploración de algunas propiedades psicométricas de las escalas de Satisfacción Vital, Felicidad Subjetiva y Auto-Percepción de Salud. In: E. Moyano-Díaz (Ed.). Calidad de Vida y Psicología en el Bicentenario de Chile (pp 447–469). Santiago, Chile. Ed. Marmor [Psychology and Quality of Life in the Chilean Bicentennial].

Moyano-Díaz, E., Cornejo, F., Carreño, B., & Muñoz, A. (2013). Bienestar subjetivo en maximizadores y satisfacedores. Terapia Psicológica, 31(3), 273–280. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082013000300001.

Nenkov, G., Morrin, M., Ward, A., Schwartz, B., & Hulland, J. (2008). A short form of the maximization scale: Factor structure, reliability, and validity studies. Judgment and Decision Making, 3, 371–388.

Nygren, T. E. y White, R. J. (2002). Assessing individual differences in decision making styles: Analytical vs. intuitive. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, Santa Monica, CA, 953–957.

Oishi, S., Tsutsui, Y., Eggleston, C., & Galinha, I. (2014). Are Maximizers Unhappier than Satisficers? A Comparison between Japan and the USA. Journal of Research in Personality, 49, 14–20.

Páez, D., Martínez-Sánchez, F., Mendiburo, A., Bobowik, M. y Sevillano, V. (2013). Affect regulation strategies and emotional adjustment for negative and positive affect: A study on anger, sadness and joy. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 249–262.

Pavot, W. Diener, E. C. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164.

Polman, E. (2010). Why are maximizers less happy than satisficers? Because they maximize positive and negative outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 23, 179–190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bdm.647.

Purvis, A., Howell, R. & Iyer, R. (2011). Exploring the role of personality in the relationship between maximization and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 50, 370–375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.023.

R Core Team. (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/.

Rim, H., Turner, B. M., Betz, N. E., & Nygren, T. E. (2011). Studies of the dimensionality, correlates, and meaning of measures of the maximizing tendency. Judgment & Decision Making, 6, 656–579.

Saffrey, C., & Roese, N. J. (2008). Praise for regret: People value regret above other negative emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 32, 46–54.

Schreiber, J. B., Stage, F. K., King, J., Nora, A., y Barlow, E. A. (2005). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. Journal of Educational Research, 99, 323–337.

Scheibehenne, B., Greifeneder, R., & Todd, P. M. (2010). Can there ever be too many options? A meta-analytic review of choice overload. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 409–425.

Schwartz, B. (2000). Self determination: The tyranny of freedom. American Psychologist, 55, 79–88.

Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1178–1197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1178.

Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 59, 99–118. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1884852.

Simon, H. A. (1956). Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review, 63, 129–138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0042769.

Sparks, E. A., Ehrlinger, J., & Eibach, R. P. (2012). Failing to commit: Maximizers avoid commitment in a way that contributes to reduced satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 72–77.

Turner, B., Rim, B. H., Betz, N., & Nygren, T. (2012). The maximization inventory. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(1), 48–60.

Unkel, S., & Trendafilov. (2010). A majorization algorithm for simultaneous parameter estimation in robust exploratory factor analysis. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 54, 3348–3358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2010.02.003.

Velicer, W. F., Eaton, C. A., & Fava, J. L. (2000). Construct explication through factor or component analysis: A review and evaluation of alternative procedures for determining the number of factors or components. In R. D. Goffin, & E. Helmes (Eds.). Problems and solutions in human assessment: Honoring Douglas N. Jackson at seventy (pp. 41–71). Boston: Kluwer.

Weinhardt, J. M., Morse, B. J., Chimeli, J., & Fisher, J. (2012). An item response theory and factor analytic examination of two prominent maximizing tendency scales. Judgment & Decision Making, 7, 644–658.

Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007). A theory of regret regulation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 3–18.

Note: Items from Diener et al., 1985.

Copyright: © 2014. The authors license this article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

This document was translated from LATEX by HEVEA.